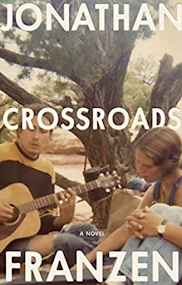

By Jonathan Franzen

CROSSROADS (2021)

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 592 pages.

★★★★

When I was young, I was involved in a Christian youth group that was the rival of a much more conservative group. Our liberalism was a point of pride, as was our equally affected hipness. The local leader dropped phrases like “Jesus and the boys (disciples)” and read from The Good News Bible, whose text now seems painfully embarrassing and antiquated. As is often the case, a lot of what passed for “cool” was shallow and transitory.

Crossroads, the newest novel from Jonathan Franzen, took me back to those days. Once you learn that the title references a similar Christian youth group, you are halfway toward an understanding of its multi-layered meaning. It is set in the imagined First Reformed Church in the equally fictional New Prospect neighborhood of Chicago. We meet the Rev. Russ Hildebrandt, his wife Marion, and their four children: Clem (19), Becky (18), Perry (15), and Judson (10). Russ grew up Mennonite, but left that faith for various reasons, chief among them Marion and his interest in progressive causes such as civil rights and the plight of Native Americans. His devotion to do-good causes won Russ many admirers, and each summer he leads work camps to the Arizona Navajo reservation where a youthful epiphany occurred.

If you pay attention to American culture, you will have observed that the popularity of causes changes over time. That’s Russ’ dilemma. Crossroads takes place in the winter of 1971 and the spring of 1972. Among middle-class white kids impacted by Vietnam, changes in style, and new musical tastes, Russ’ coolness has faded like the allure of his ever-present sheepskin coat. Young people are flocking to First Reformed, but to Crossroads, which is led by a new groovy pastor, Rick Ambrose. Russ pours out his fall from iconic status thusly,

"What galls me about so-called youth culture now is that people seem to think it came out of nowhere. The kids today think they invented radical politics, invented premarital sex, invented civil rights, and women’s rights. Most of them have never even heard of Eugene Debs, John Dewey, Margaret Sanger, Richard Wright. When I was in Birmingham in 1963, a lot of the protestors were my age or older. The only real difference now is their fashions–different music, different hair. And that’s just superficial."

The Crossroads group takes on aspects that blend cult-like behavior, pop psychology, and worldliness; and the novel takes a dark turn. What begins as a look at a youth group veers into many other things, including the backstories of troubled individuals. This is one of those novels in which the lines between sincerity and fraudulence are blurred–not just for the Hildebrandts, but for pretty much everyone around them as well. Flashbacks to the past make us wonder if all those problems are bred in the bone. Readers also come to realize that religion is merely the fulcrum that lifts the veil from other things: the thin line between righteousness and sin, faith versus mere ritual, clashing cultural values, purity and lust, addiction of all sorts, secrets well and poorly kept, coolness versus goodness, and how easy it is to drift if one is never fully present in the first place.

Many novelists build toward revelations and resolutions. Not Franzen. When you come to a metaphorical crossroads and paths diverge, which one does one take? Writers who make that choice clear and easy do a disservice to the human condition; it’s often hard to know the right path until one is far enough along to discern the consequences looming in the distance. If you need things tied together with a neat bow, look elsewhere. Not even Native American characters come across with much nobility. I will also warn that Crossroads is not a quick read. Frankly, the book did not need to be as long as it is, but it is nonetheless a provocative book.

Is Franzen a realist or a cynic? That’s your call, though my vote goes for option A. Either way, though, Crossroads is a reminder that belief in anything should be rooted in things more substantive than fashion or bandwagon behavior. If it goes no deeper than a desire to be placed on a pedestal of coolness, it will not survive when the cultural winds shift.

Rob Weir

No comments:

Post a Comment