JOSÉ GUADALUPE POSADA:

SYMBOLS, SKELETOND, AND SATIRE

Clark Art Institute

Williamstown, MA through October 10, 2002

|

| Calavera Katrina |

The name might not register, but José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913) is Mexico’s most-proclaimed graphic artist. Even if you don’t know his name, you’ve likely seen at least one of his works: Calavera Catrina. Calavera translates as skeleton and Catrina is the female version of a dandy. Still stumped? Have you ever seen a Grateful Dead poster or album cover? The Dead plastered Calavera Catrina on everything.

|

| Happy and Wild Party |

The Mexican fascination with skeletons baffles many people. Why focus on the grim subject of death and decay? First of all, Mexico has long been a Roman Catholic-dominated society. Calaveres are reminders that the flesh and earthly pleasures are supposed to view as transitory and shouldn’t be one’s focus. You find skeletons engaging in all manner of pleasure–as in Posada’s Happy and Wild Party of All Calaveres—a symbol that there is an afterlife. Second, Catholicism was subject to syncretism, a fancy word that means its beliefs were influenced by older ones. The danse macabre was a prevalent image that emerged during Europe’s Black Death during the 14th century and likely came into Catholicism via older pagan and folk beliefs, like the pharaonic Egyptian view that the soul can inhabit tomb figurines. Mostly, though, in celebrations such as the Day of the Dead (November 1-2) animated skeletons reinforce the hope that when humans perish, their souls will persist.

|

| Oaxaca symbol |

|

| Hard to miss from this distance! |

It should thus not surprise that Posada drew calaveres in all kinds of situations: riding bicycles, as a symbol of Oaxaca, or even as representations of revolutionary figures such as Emiliano Zapata. Posada managed to stay out of trouble during a very chaotic period. As in the French Revolution, the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) was presaged by turmoil and then went through various phases in which the top dogs ended up on the wrong side of firing squads and garrote poles. Porfirio Diaz modernized Mexico, but was an autocrat with a penchant of turning former allies into rebels. It didn’t help that the United States meddled in the game of musical leadership chairs. (Just before World War I, the US sent General Pershing more than a thousand miles into Mexico in pursuit of bandito Pancho Villa.)

|

| Zapata |

|

| Slanderous Girl Taken by the Devil |

|

| End of the World |

Posada used humor and satire to give the appearance of neutrality. His real views often came in his illustrations that accompanied corridos (ballads), many of which honored Mexican folk heroes such as Zapata and Villa. He also illustrated corridos written to comment on other things; the corrido is one of Mexico’s oldest folk music and poetic traditions. He played his cards shrewdly. Slanderous Girl Taken by the Devil appeased the Church, but his End of the World played better with neopagan outlooks. (Comets such as Haley’s often led the masses to imagine apocalyptic fates.)

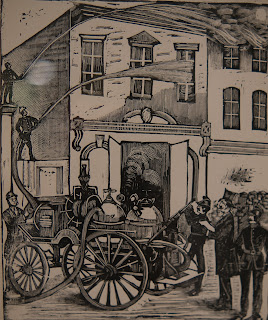

Posada’s other big role was that of a news illustrator. Photographs were often either unavailable or failed to arrive in time to satisfy what we today call “instant news.” Posada drew upon written accounts and used his imagination to fill in the proverbial blanks. An example of this is his illustration of firefighters trying to put out a blaze.

His legacy includes the inspiration other artists drew from him. It’s an impressive list that includes Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco, and Diego Rivera. Speaking for myself, I often give short shrift to graphic artists. Posada might just help me break that bad habit.

Rob Weir