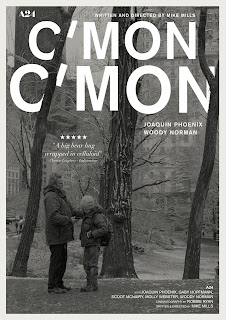

C’MON C’MON (2021)

Directed by Mike Mills

A24, 108 minutes, R (language)

★★★★★

C’mon C’mon won a host independent film festival awards, yet few have seen it. Too bad; it is a masterful piece of work. I’m not one for forced sentimentality, especially the mainstream habit of using cute kids as cheap ploys to gain audience sympathy. C’mon C’mon features nine-year-old Jesse (Woody Norman), but the efforts of director/writer Mike Mills ring true because Mills based the script on his relationship with his own son.

Johnny (Joaquin Phoenix) is a radio journalist/soundscape artist whose current project sends him around the country to record kids talking about the future, their hopes, fears, and what adults don’t get. Johnny is in Detroit where, as you might imagine, kids are more savvy about their expectations, but he’s about to be removed from his detached observer role. Johnny gets a phone call from his sister Viv (Gaby Hoffmann) in Los Angeles. She needs her aloof bachelor brother to watch Jesse, because she must go to Oakland to place her husband Paul (Scoot McNairy) in a facility. (Paul has long suffered from mental illness.) She’s at her wits end and isn’t sympathetic to Johnny’s pleas that his work and travel schedule are too heavy.

Johnny’s guilt trip is the first leg of a journey that will take him and Jesse to New York, back to Los Angeles, on to New Orleans, and into new levels of awareness. He and Viv are also trying to recover from their mother’s death from dementia, plus Johnny has effectively shut down his emotions in an attempt to get over a breakup with his longtime girlfriend. None of this is a good foundation from which to build a relationship with a nephew he barely knows. Nor does it help that he lives in New York, nearly 2800 miles from his sister and her family. In all, he must also face the fact that he listens to kids talk, but often fails to hear what they are saying.

In (too) many movies, adults and children come to like each other through contrivances that are as phony as a sincere-sounding politician. This film takes its time to move from distrust to dislike to reluctant acceptance before any deeper bonding occurs. What would be a good way to start this venture? How about letting the kid mess with the recording equipment? Or take him on the road with you? Johnny is also able to draw on the interpersonal skills of his sound team, Fernando (Jaboukie Young-White) and Roxanne (Molly Webster)* to fill in his considerable emotional and attention gaps.

This is a beautiful film. The word “empathy” repeatedly appears in reviews and deservedly so. You probably don’t need me to tell you that Joaquin Phoenix is a terrific actor, but if you know him best for his role as the demented genius villain in Joker (2019), he will stagger you in C’mon C’mon. Physically he looks like Steve Bannon at his disheveled worst. He admittedly has better intentions than Bannon (who doesn’t?), but he’s not much more in touch with reality. Phoenix is so convincing when he drifts out of his depth and comfort zone that we shiver as if we are inside his skin. Ditto when we watch him literally get down to Jesse’s level while fossicking for connections or a way out an unsettling moment.

Watch for Woody Norman; this kid has chops. He’s 12 now, but plays nine-year-old Jesse as an enigmatic mix of precociousness and vulnerability. Kids can turn on a dime between engaged and enraged. When Jesse wants attention, he wants it now, not “in a minute.” Such situations don’t go down well in Midtown Manhattan. When Johnny doesn’t respond to him right away and an angry Jesse wanders off, their mutual panic is so palpable that once again we too feel it.

C’mon C’mon is in black and white, which adds to its verisimilitude. People live in color, but black and white provides the proper contrasting frame for Johnny, Jesse, Viv, and Paul. Each is in limbo between being and becoming with black-and-white hard edges defining their present, but the future remains foggy. Cinematographer Robbie Ryan and Mills know exactly when to zoom in to depict understanding and when to shake the camera for tension or pull it back for missed communications.

This small film is lovingly rendered at each critical moment. It is a statement of creative and artistic vision that leaves you feeling good, but not in a mawkish way. Nor is it a what-adults-learn-from-kids film, rather one in which they shape each other.

Rob Weir

* Molly Webster is actually a radio journalist in real life.