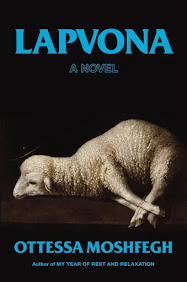

LAPVONA (2022)

By Ottessa Moshfegh

Penguin, 304 pages

★★★★

Lapvona, the fourth novel of Boston-born novelist Ottessa Moshfegh, is a strange book. Moshfegh has an unapologetic taste for the macabre and unsavory, which means readers will be either thrilled or unnerved.

Lapvona references a small fiefdom whose outward setting is medieval, perhaps during the tail end of the Black Death. It’s also, though, a satirical allegory of capitalism and the ways in which corruption and community collide. Moshfegh is on record as saying if the book has a moral, it’s a rejection of the ancient Roman notion that human fate is controlled by Fortuna, the goddess of luck. In her worldview, belief in random fate is a convenient cover for conscious choice.

Moshfegh is a skilled stylist, but this doesn’t make her plotlines easy to decipher. She blends plausibility with elements suggestive of magical realism and delves into themes of superstition, dreaming, bewitching, and cannabis use. Lapvona also makes use of extended metaphors of sight versus blindness and the thinness of barriers between life and death and the natural and spirit worlds.

Marek is the centerpiece of the novel. He is the son of Jude, the village shepherd, who has mixed feelings about the physically deformed Marek. His ugliness is remarked upon by villagers–until it’s not. His lambs are Jude’s biggest love since his wife disappeared; he is deeply anguished whenever he must sell some of them for meat to mysterious Northerners.

Lapvona is controlled by Villiam, a local lord, who is vain, profligate, clueless, and corrupt. His son Jacob is Marek’s opposite: handsome, immaculate in dress, and well-educated. Marek and Jacob are also related despite their social gulf. Villiam really cares only for himself, so when Marek kills (accidently or not!) Jacob, Villiam simply takes Marek as his son. Other major characters include Villiam’s wife Dibra and her horseman lover Luka; Lispeth, who was betrothed to Jacob and becomes Marek’s resentful serving girl; Father Barnabas, a faithless priest interested in luxury and power; Agata, Jude’s ex-wife who reappears after 13 years; and Grigor, a peasant with contempt for the rich. Bandits also play a role, though they are undefined and may actually be in cahoots with Villiam. Finally, there is Ina, a blind old woman (witch?) who has never been pregnant yet has been a wet nurse for decades.

Like Monty Python’s Camelot, Lapvona is a land in which the powerful enjoy the fruits of life and the peasants stink from sweat and layers of various varieties of excrement. The book is arranged calendrically, from spring to spring. The first spring finds the land verdant, Jude cuddling his lambs, and Jude’s relief to be rid of Marek.

Summer invites Covid comparisons. A horrible drought parches the land and brings starvation, raids, decimation of pets and livestock, villagers reduced to eating mud, and cannibalism. Dibra and Luka exit, and Ina ends up with the eyes of a horse that restores her vision and causes her to reverse aging. Of course, not everyone starves; Villiam, Barnabas, and Marek eat very well, the later transforming himself into a little tyrant in his own right. (And suddenly no one comments publicly on his deformity!)

Fall sees the return of rain and the impact of Agata’s return. She has been a servant in a nunnery and is now tongueless and pregnant. When she is examined and declared a virgin–she’s assuredly not–Villiam marries her in the superstitious belief that she is bearing the new Christ child and he will become the new Joseph. All that’s crystal clear is that neither Agata nor Jude want anything to do with Marek.

Winter sees Marek’s descent into alcoholism, the death of Villiam, the demise of Father Barnabas demise, and the dismantling of the church. The new spring finds Ina increasingly youthful and Marek the lord of the manor, but you should not anticipate happily-ever-after in a book such as this. The ending is ambiguous, but might be the most horrifying thing in the book.

Lest you think I’ve given away too much, know that the plot is window dressing for the aforementioned themes that run throughout the book. In other words, it’s the context, more than the narrative, that makes Lavona tick. Moshfegh has both admirers and those who find her work repulsive. I can only assure you Lavona is not cut from threadbare cloth and that you will contemplate the meaning of its cover art.

Rob Weir

No comments:

Post a Comment