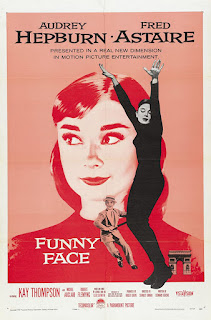

FUNNY FACE (1957)

Directed by Stanley Donen

Paramount, 103 minutes, Not-rated.

★

Audrey Hepburn was an icon and Fred Astaire one of the smoothest dancers and leading men in Hollywood history. Despite that, some films wear like iron and others are pieces of disintegrating tulle from bygone costume failures. Funny Face is one of the latter.

This musical comedy began life as a 1927 Broadway play and that's about the time that Astaire was young enough to have been involved in such a project. When it was turned into a movie 30 years later, Astaire was 57-years-old, which made his romance with 28-year-old Audrey Hepburn so creepy that not even dollops of Paris and Hollywood magic could gloss it. Nor were Ira and George Gershwin at the top of their game when they reworked songs from the show and wrote new ones for the film. Only “How Long Has This Been Going On” had much of a shelf life and it only after later being re-tailored as a smoky torch ballad. (“S'Wonderful” was popular for about half a season.) Watching Funny Face now embodies the British term naff, meaning insipid.

I grant that it had wonderful set design. The story revolves around Quality Magazine, a fashion rag along the lines of Harper's Bazaar or Vogue. It is simultaneously an advertisement and a lampoon of such publications. Editor Maggie Prescott (Kay Thompson) is a stand-in for Diana Vreeland and Dick Avery (Astaire) of photographer Richard Avedon. Maggie is bored by the magazine's new issue, the setup for the opening musical number “Think Pink” in which she successfully convinces American women that pink is the only color they should wear (though she hates it). Thompson's romp in the high-contrast minimalist office is visually stunning.

Still, Maggie thinks the magazine needs intellectual heft but her models, including Marion (Dovima, one of several actual models in the film), are airheads who wouldn't know Plato from Play-Doh. She dispatches Dick to scout locations for a makeover and he and his pink-clad female crew commandeer a Greenwich Village philosophy bookstore. They rearrange books, and make a mess over the feeble protests of mousy clerk Jo Stockton (Hepburn). Jo is appalled by the vacuousness of the fashion world and is devoted to an empathicalism worldview, especially as espoused by French thinker Professor Flostre. (It's basically empathy draped in mumbo jumbo.) Jo's life is disrupted again when Dick convinces Maggie that Jo's “funny face” is exactly what Quality needs.

How do you convince a beatnik intellectual like Jo to become a supermodel? A trip to Paris, of course. The magazine wants her to debut the new line of French designer Paul Duval (Robert Flemyng [sic]) but Jo relishes a chance to hang out in smoky cafes and perhaps meet Flostre. Add musical numbers, a burgeoning romance between Jo and Dick, contrivances that keep them apart, fashion runway scenes, and the illusion that Jo and Dick are ill-suited, and that's Funny Face in a nutshell. It's A Star in Born in 1950s couture blended with a bit of Romeo and Juliet.

Astaire was past his prime in 1957. His dancing seemed limp and lifeless, even when he pulled cool moves with an umbrella. His acting was equally flat. The less said about Hepburn's spasmodic cafe moves the better. (If you think Maynard G. Krebs on the Dobie Gillis sitcom demeaned the Beats, it's reverential by contrast.) Hepburn was, of course, cute as a button-festooned rabbit, but her dancing also invites the descriptor naff.

In its day, Funny Face got good reviews, with only the London Times having the courage to dismiss it as fluffy nonsense. Audrey Hepburn became a beloved screen star, which helps explain why Funny Face is often accorded “classic” status. Don’t be fooled; this fashion-driven antique is like finding an old snapshot of yourself attired in clothing you'd deny ever having worn. Aside from eye-candy sets, one of its few pleasures is watching Kay Thompson connive, throw fits, and dance. If her name sounds familiar, she was also the author of the children's book series Eloise.

At the risk of offending anyone in a May-December relationship, the wooing of Hepburn by Astaire is more than distressing; it's thoroughly unconvincing and could have only been made during that part of the 1950s in which a woman “needed” a man and anyone who showed interest would do. Hepburn falls for Astaire after one kiss, her first we are led to believe. Because, of course, who would want to kiss Hepburn? (Take a number!) Funny Face is an artifact from the past best left in a film vault.

Rob Weir