Sandy Denny: An Appreciation

|

| 1947-78 |

I heard some good new music this month, but nothing blew me

away. It’s an opportunity to crawl into the Way Back Machine for my artist of

the month: Sandy Denny. Sandy is my favorite female vocalist of all time.

Was she the best ever? That question, surely, covers too many genres and too

many personal tastes. I will say, though, that her “Who Knows Where the TimeGoes?” is my favorite song and is surely one of the greatest folk songs ever

pressed onto vinyl. (I can't hear it without tearing up.)

Denny (1947-78) gets labeled a “forgotten” singer. That’s not accurate, but it is true that she was better known in the UK than in North America. For rock fans, hers is the voice dueling with Robert Plant on the Led Zeppelin song “The Battle of Evermore” and, for once, Plant met his equal. Sandy was better known, though, as a pioneer of folk rock.

She didn’t invent it–the label was first used in 1965 to describe The Byrds–but Denny was one of the first to update “traditional” music, not just singer/songwriter compositions. She made her first two recordings for the Saga label in 1967 before joining the rock band The Strawbs. With them, she began performing “Who Knows Where the Times Goes.” Judy Collins heard a demo tape and covered it, which helped propel Denny’s career. The Strawbs, though, were basically a second-tier band–its best player was/is guitarist Dave Cousins–that wanted to rock out. Remember Joni Mitchell’s line “you don’t know what you’ve got ‘till it’s gone?” Sandy and The Strawbs parted ways over creative differences and Sandy went in search of simpatico musicians.

|

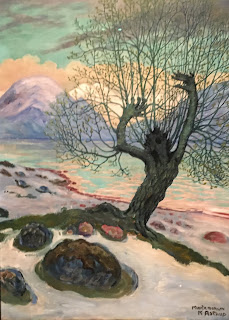

| Check out the guy on the right! |

She landed in Fairport Convention, which needed a new

lead singer. Denny might have passed on them, had they not hired a teenaged

guitarist whose talents Sandy thought were equal to her own. Arrogant? What if

I tell you that guitarist’s name is Richard Thompson? She joined a lineup that

included Thompson, Iain Matthews, Ashley Hutchings, and Simon Nicol, a

veritable supergroup. Between 1968-70, Denny was on three Fairport albums. The

first was slightly tentative, but included a wonderful original titled “Fotheringay”

and a terrific remake of “She Moves Through the Fair.”

Fairport hit their stride with the next album, Unhalfbricking, which included “Who Knows Where the Time Goes?” “A Sailor’s Life,” and Thompson’s “Genesis Hall.” Then came Liege and Leaf. If you don’t know this record, there’s an Alaska-sized hole in your musical education. Sandy’s take on "Reynardine” “Matty Groves," and "Tam Lin" are both definitive and unparalleled. She proved that songs whose origins might go back as far as the Middle Ages could become rock songs. She also defined Thompson’s “Crazy Man Michael” and originals such as “Come All Ye.” To get a sense of how she and Thompson meshed, listen to “Tam Lin.” It’s a good Halloween song, as it tells of how the faeries kidnap knights, but paraded them on October 30. Anyone–young Janet in the song–who can grab on to a knight and maintain their grip as the knight shape shifts through monstrous forms redeems that knight. It is seven plus minutes of spooky mystery and joy.

In 1970, Sandy left Fairport to form Fotheringay with future husband Trevor Lucas because she wanted to do more original songs. Five of the nine tracks on their one album were from her pen, my favorites of which are “Winter Winds” and “Nothing More.” Ironically, though, the standout track is another traditional, “Banks of the Nile.”

This lineup was sunk by a dispute with notoriously controlling producer Joe Boyd. She formed a new band–that included Thompson, Conway, and Dave Richards–and, in 1971, released what is arguably her best “solo” album: The North Star Grassman and the Ravens. It had seven originals, my favorites of which are the title track, “John the Gun,” and “Late November,” but again it was her reimagining of a traditional that stands out: “Blackwaterside,” a song some might know from the Irish band Altan. She also rescued an old Brenda Lee hit “Jump the Broomstick.”

She followed with Sandy in 1972, a nice record, but somewhat subdued. I recommend “Sweet Rosemary” and “It Will Take a LongTime” from that one. The heavily airbrushed cover, though, presaged a major misstep. In 1973, Lucas produced Like an Old Fashioned Waltz that found Denny in a standards moods, even though she wrote six of the eight tracks. The song “Solo” is considered the best, but the album is marred by mawkish orchestral strings, plus who wants to hear Denny sing Fats Waller? Lucas dropped the production ball.

Denny rejoined Fairport in 1974, left again, burt reunited with several members, including Thompson, for two records that came out in 1977: Rendezvous and Gold Dust, the second of which is most of the material from the first, plus eight other originals, a live recording of what turned out to be Sandy’s last concert. Standout tracks include Denny kicking it in high gear to cover Thompson’s “I Wish I was a FoolFor You” and “Gold Dust,” the latter of which she sounds a lot like Grace Slick. The concert recording features her in a full rock n’ roll mode. She was good at it, but she was better at folk rock.

Alas, Sandy was also spiraling out of control by then. She had given birth to her only child, Georgia, but her marriage was tumultuous, she was depressed, her health was fragile, and she drank heavily. By all accounts, she was not a good drunk. She unraveled when Lucas took Georgia and moved to his native Australia without telling her. She died on April 21, 1978, from brain trauma resulting from a fall down a set of stairs. That was 43 years ago. Indeed, who knows where they times goes?

Rob Weir