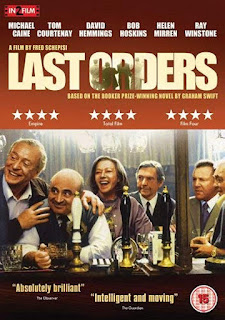

LAST ORDERS (2001)

Directed by Fred Schepisi

Columbia TriStar, 106 minutes, R (language), in Cockney English

★★★★

Last Orders is an adaptation of Graham Swift’s 1996 Booker Prize-winning novel of the same name. It is an excellent example of how well Brits do ensemble movies. Of course, it helps to cast with actors of the gravitas of Michael Caine, Tom Courtney, Bob Hoskins, David Hemmings, Helen Mirren, and Ray Winstone.

Director Fred Schepisi wisely made Last Orders as a classic “small film,” meaning it doesn’t try to dazzle you with intricacies of plot, cinematography, or production. Rather, it is a character study of friends whose relationship is kept together as much by inertia as common interests. The title holds a dual meaning. In British pubs it’s the equivalent of last call; that is, the bar tender’s announcement that it’s the final chance to order drinks before closing. In this case, though, it also means a duty. Jack Dodds (Caine) has died and his old compadres are charged with taking his ashes from London to Margate to be scattered in the sea.

In other words, The Last Call is a road trip that’s filled with flashbacks, squabbles, remembrances, irreverence, and poignancy. As we quickly surmise, Jack, a former butcher, was the glue that kept unlikely associates together. Jack wasn’t a saint, but he was a good person, and the same is questionable about the company he kept. In World War II he battled alongside Ray “Lucky” Johnson (Hoskins), a punter who spends most of his time wagering on horses. He is joined by Lenny (Hemmings), a former boxer who didn’t leave his fists in the ring, and Jack’s pretentious son Vince (Winstone), a dealer in posh used cars who–to his annoyance–is treated as if he’s still a kid by the others. There’s also Vic Tucker, a mortician who tries his best–mostly unsuccessfully–to play the role of ego to Ray’s superego and the ids of the other two. Along the way they meet up with Jack’s widow Amy (Mirren), who is on her way to visit her developmentally challenged daughter who has been institutionalized for over 50 years.

The journey is marked by numerous aforementioned flashbacks (with younger actors as stand-ins). As is often the case with youth, none of them had their lives figured out back then, but they were more vital before responsibilities, work, and cynicism redefined them. Arguments abound–often instigated by sharp-tongued Ray–punctuated by good old Jack stories. Son Vince would just like to get the whole thing done and dusted, but what’s a road trip without detours? It’s only 76 miles from London to Margate and can be done in under two hours, but not if you take side trips to Canterbury and the Chatham Naval Memorial, and certainly not if all wars of words are defused at pub stops.

Let me emphasize again that the storyline is spare. This film only works if you cast skilled actors who can hold audience attention through the sheer force of their craft and personalities. Any one of veterans such as the principals could recite from actuarial tables and you’d be enthralled. Despite the glum task of dumping Jack into the English Channel, Last Order is often very funny. After all, what’s more ripe for lampoon than a carful of guys lacking in filters and self-awareness? Yet because they have a solemn mission, the humor is leavened with ouch! moments in which pathos intervenes.

Last Orders is ultimately a film that rests on verbosity, wit, and inference. The side trips are not so much tourist travel as diversions that challenge the living to confront the mundanity of their post-Jack selves. It’s a bit like That Championship Season without basketball. I liked it quite a lot, though I had to swallow the biter pill that neither Hoskins nor Hemmings are with us any longer.

Rob Weir