IMPRINTED: ILLUSTRATING RACE

Norman Rockwell Museum

Stockbridge, MA

Through October 30, 2022

Is it possible to make a point too well? The Norman Rockwell Museum is currently displaying a powerful exhibit titled Imprinted: Illustrating Race. Early on we see a 2018 work from Thomas Richman Blackshear II titled A Common Thread. We see individuals of African American, Asian, and Native American heritage fronted by an exotic female figure who looks as if she might have escaped a Gustav Klimt painting. Each holds a candle, which suggests the exhibit will shed light on how race is depicted.

In 1944, the Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal published An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. More’s the pity that the issue he highlighted 78 years ago–white oppression of peoples of color–persists. Systematic racism is a major reason for this, a term that alerts that racism is so tightly woven in the fabric of American society that many people no longer “see” it, and those who do find it hard to disentangle enough threads to make it unravel.

Imprinted reminded me of the unexamined systematic racism of my elementary school years–like illustrations for Little Black Sambo storybooks. These were in wide circulation and were even read aloud in school. They were first written by a Scottish woman and Sambo was supposed to be South Asian, shades of British imperialism. Sambo, though, resembled a golliwog, a black rag doll that caricatured black features. Golliwog dolls and books in turn took were inspired by minstrel shows in which (mostly) white entertainers donned blackface to lampoon African Americans. Thus, white American saw Sambo as African American, as he resembled golliwogs and all-too-present blackface acts.

This set the tone for numerous other disrespectful ways people of color were depicted. Consider the above ad for Cream of Wheat in which a smiling black man is infantilized to the level of the white blunderbuss-toting toddler at his side. Norman Rockwell’s 1946 Dining Car captured the same man-to-child implications.

Smiling subservient black folks were once trademarks for products such as Uncle Ben’s rice and Aunt Jemima Pancake mix. If you can believe it, when I was in second grade a black woman wearing a kerchief visited our school as the “real” Aunt Jemima. The entire school was ushered into a room to gawk at her. (She was most assuredly an actress handed a very bad gig!) For sheer offensiveness, though, it's hard to top British soap maker Pears. The image speaks for itself.

Here's where things get complicated. The Rockwell show has over 300 images from the 19th century to the present. To return to the Blackshears work, by trying hard to be inclusive several problems arise. The first is a drive-by issue. Themes of Orientalism, negative views of immigrants, and discrimination against other non-white peoples are given short shrift. The images educate–one including an Irishman serves notice that “whiteness” isn’t a given–but the unintentional suggestion is that discrimination against African Americans holds primacy. It is indeed an American dilemma, but it is slippery turf to imply rankings of oppression. (The Chinese, for instance, were even more reviled during the late 19th century.) The show would have been stronger had it not strayed upon turf it could not cover thoroughly.

| |

| Gary Kelley "Nina Simone" |

|

| Gregory Chrsitie "Coltrane" |

|

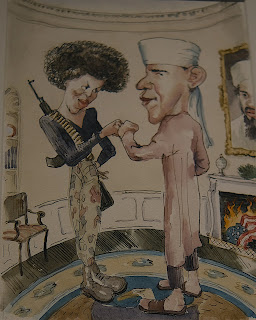

| Blitt's controversial "Fistbump" |

A larger problem is that Imprinted is overwhelming. A Swiss friend with less grounding in American history expressed feeling bludgeoned before she entered the second gallery. The images are powerful, but I think less would have been more. By the time one gets to positive images of black life in gallery three, the viewer is emotionally spent. Thus, we recoil in horror before Barry Blitt’s Fistbump (2008), which shows Barack and Michelle Obama as terrorists burning an American flag in a fireplace with Osama bin Laden’s portrait hanging above the mantle. The irony is that this is a New Yorker illustration in which Blitt sought to lampoon Obama alarmists. Yet it’s understandable viewers might misunderstand after being saturated with negative depictions. Many, I’m sure, were so exhausted that they long stopped reading accompanying wall placards. (For the record, I echo those who find Blitt’s illustration problematic.)

|

| Kadir Nelson |

I also observed people rushing through the exhibit In Our Lifetime: Paintings from the Pandemic, which spotlights the heralded Kadir Nelson. Maybe this should have been the first gallery. Nelson is a Los Angeles-based artist whose work has graced postage stamps, New Yorker covers, Dreamworks projects, galleries, and museums. He offers an America that could/should be, one that includes confronting its past, but finds room for people as people. Two paintings of kids drive home the point in Rockwellian fashion. Stickball shows a determined boy who just happens to be black ready to take his best cut. If the little girl in Sweet Liberty had been white, one might call the painting mawkish. Because she is black, though, we see it for what it is: a call for America to follow its better angels.

Rob Weir