Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA

Though July 27, 2025

I’ve not made an exhaustive study of this, but I suspect that Edvard Munch (1863-1944) is the most famous painter in Norwegian history. Who does not know “The Scream” (1893) or the slightly less famous “Ashes” (1894) and “Vampire” (1895)?

You’ve probably noticed that in museums these days that you can buy posters, postcards, coffee cups, t-shirts, and all manner of gear bearing images originally created by famous artists. There are those who call such things tacky, but in truth the horse left the barn as soon as it was technically possible to reproduce such works. A current Munch exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums explores the technical aspects of his “branding,” as it were.

Of course, in Munch’s time reproduction was technologically more difficult, no one wore art-shirts, and adorning something as practical as a coffee mug with a famous painting would have been considered crass. That said, if you look at what we do today it shares a characteristic with Munch’s reproductions: the quality varies tremendously in accordance with the materials, machinery, and tools used to create them–not to mention the original source used. (Was it a painting by someone trying to recreate the artist’s style? A line drawing? A copy of a copy in a book? A chalk study? An earlier work that was altered in the final version?)

The most common forms of reproduction in Munch’s time were woodcuts and lithographs; that is, one carves a wooden surface, inks the colors separately, and presses it onto another material (paper or linen usually), or etching a stone and doing the same. Each has its virtues–I sometimes like woodcuts better than the painting–but it’s hard to capture the exact colors the artist used with ink or prepare the surface carefully so it doesn’t smudge, run, or dry too fast.

Munch was like a writer who does multiple drafts. Consider “Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones)” (1906-08). He originally did a painting in 1892 that was printed. The first painting was destroyed and he worked on a new version from 1906-08, but reversed the position of the man and the woman. Scholars believe he did so because he worked from a woodcut of the original.

“The Seashore” isn’t one of Munch’s better known works, but if you look up the original you’ll see that it is of an old woman and a younger one on a beach. In the lithograph (probably unfinished) the older woman looks like Death and her features are indistinct. If you’re not sure what a lithograph looks like, here’s one and it’s a substantial chunk of rock.

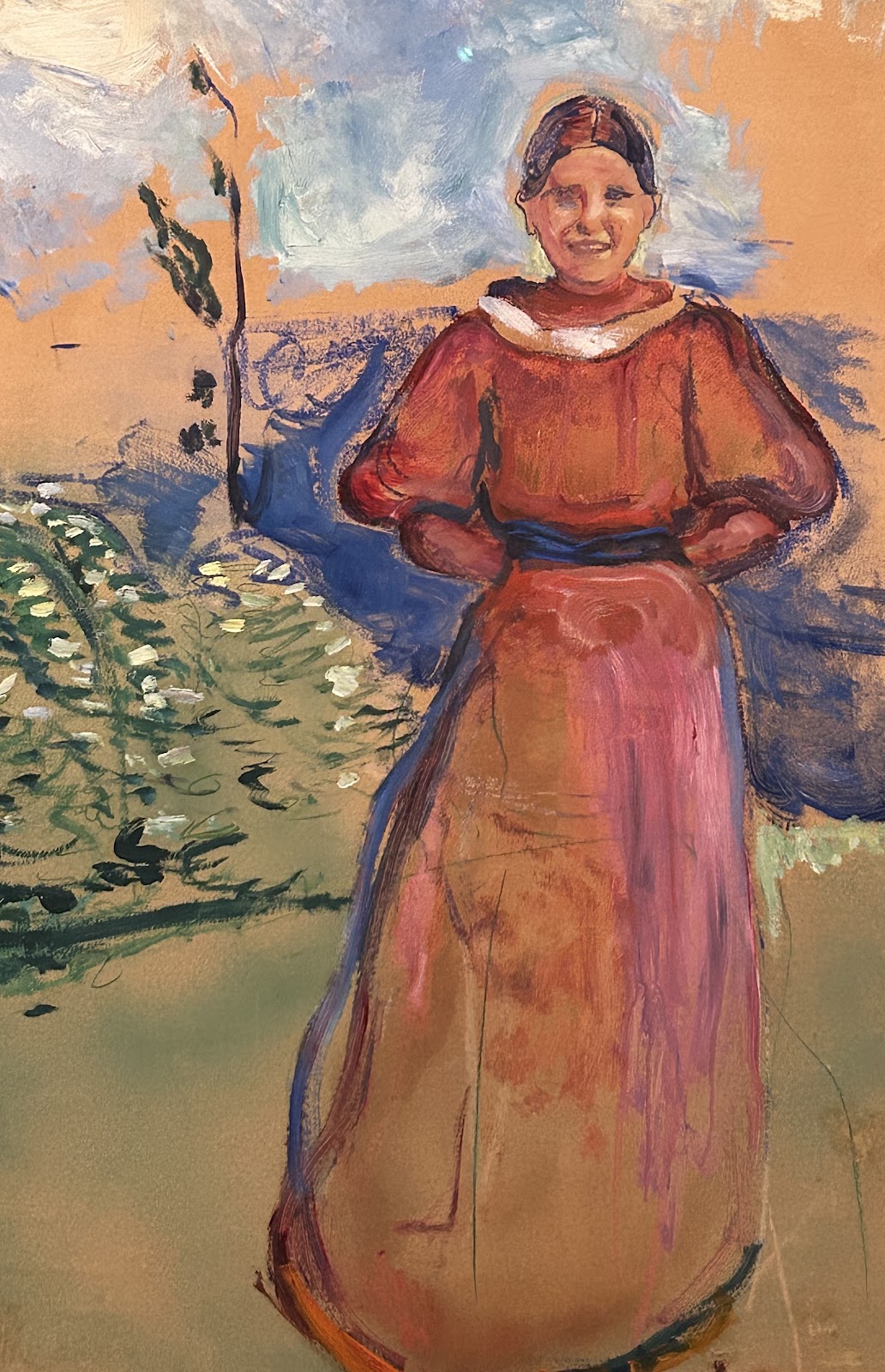

Speaking of rough drafts, Munch did this “Inger in a Red Dress” (1894) on a piece of cheap board. (Inger was a photographer and his youngest sister.) It’s quite different from the final painting. This one was done with wet-on-wet painting and was done when he was just beginning to make prints. You might (sort of) recognize this Munch lithograph. It looks a bit distressing, but the painting was titled “Madonna.” Not all versions of the prints looked all that that divine! Some had the child (embryo?) in the lower left and many did not. Munch made multiple versions as if he were tinkering with mood and subject.

As x-ray radiology proves, “Winter in Kragero” (1915) was altered numerous times. Is finished? Unclear. Was it intended for some other purpose? Very possibly. It bears similarity to an earlier oil painting, “Old Fisherman on Snow-Covered Coast” (1910-11), though it too has been painted over and the fisherman bears resemblance to a woodcut he did of his neighbor.

This self-portrait gives pause for thought as well. It’s a woodcut; Munch did many of himself, but each has an unfinished quality about them. Did he do this for effect? Self-loathing? Did he just lose interest? Because the print would be more dramatic? Again, it’s a conundrum, but cheap reproductions–sometimes called “chromos”–were quite popular among the masses and it’s usually a good idea to follow the money!

This Munch exhibit reminds us that past technology and that of the present also share similarities of intention and marketplace pressures. We claim that we can do a lot more things today–if we can find the time to do them. I suspect Munch would agree.

Rob Weir

No comments:

Post a Comment