FABRIC OF A NATION: AMERICAN QUILT STORIES

Through January 17, 2022

PAPER STORIES, LAYERED DREAMS: THE ART OF EKUA HOLMES

Through January 23, 23, 2022

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

It had been 18 months since we last entered the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and for our first trip back, we decided to concentrate on just a few shows. So, let’s cut to the chase.

Cut is a good segue to Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories, a look at what sewing projects tell us about our past and ourselves. Some of the quilts were “folk art” and others might be classified as “fine art.” I’ve never cared much for such distinctions. Some of the quilters are known in the stitcher community. One is Bisa Butler, whose To God and Truth (2019) depicts the Morris Brown College baseball team. She makes us see the hues among African-Americans by rendering “black” faces in vibrant colors.

|

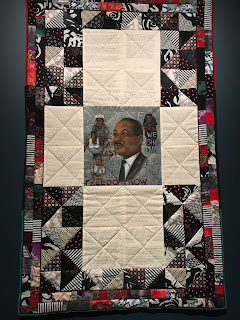

| Faith Ringgold |

Another well-known artist (in numerous media) is Faith Ringgold. Her Martin Luther King and the Sisterhood is self-explanatory. Some might also know the name Lillie Mae Pettway, a link to the Gee’s Bend, Alabama quilters whose work has gotten a lot of belated recognition.

Housetop is a 12-block pattern with variations.

|

| Lillie Mae Pettway |

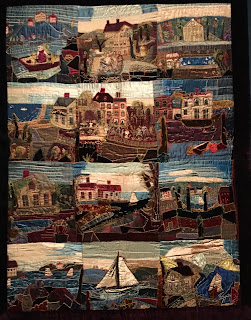

The MFA exhibit samples three centuries’ worth of quilts that indeed tell tales. The show is strongest in highlighting people of color and LGBTQIA communities. This is revelatory given that many of the quilters are unknown or forgotten. One quilt points us to reasons to recover their stories, as it depicts various ways in which those outside the mainstream have been (mis)represented. Still others make statements through the sheer skill that went into creating such meticulous work, including one from an unknown Amish stitcher and one from Celestine

Bacheller titled Pictorial Quilt (c. 1880).

|

| Celestine Bacheller |

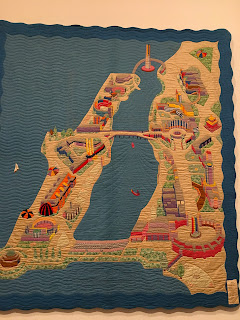

World’s fairs occasionally spotlight the work of those on the social margins. Some of that has been a sly dance of tokenism, a way to trumpet American progressivism without actually being progressive, yet the art speaks for itself. Edith Morrow Matthews contributed The Spectrum, a trippy quilt that presaged op-art at the 1933 Chicago fair. Richard Rowley quilted the fair’s map in fabric: A Century of Progress.

|

| Matthews above/Rowley below |

There are a surprising number of men represented at the MFA show, including the well-known Sanford Biggers, though his work pushes the boundaries of what we think of as a quilt. Most visitors will probably relate best to overtly political works that require little explanation to (if you will) unravel. Carolyn Mazloomi mused upon a famous song about lynching for her Strange Fruit II and Sylvia Hernandez put thread to needle to ask the question about gun violence that rests upon many lips: How Many More? Edward Larson and Fran Soika cram a lot of troubled politicians into a 1979 work titled Nixon Resigns.

|

| Carolyn Mazloomi |

|

| Sylvia Henandez |

Two intriguing works caught my eye. Sabrina Gscwandtner’s Camouflage lives up to its title. Those in a hurry could walk right past it without realizing it is made of discarded 16mm film strips. The most in-your-face work belongs to Agusta Agustsson whose Blanket of Red Flowers makes tangible the phrase “banned in Boston.” It was removed from its first viewing in 1979, as it represents alternating blocks of male and female genitalia. Note the date. It came at the dawning of the AIDS crisis, though its meaning is broader than that.

|

| Camouflage |

|

| Banned in Boston! |

If works on paper haven’t caught your attention before, check out a retrospective culled from book projects illustrated by Roxbury artist Ekua Holmes (b. 1955). She celebrates the positivity of blackness in various ways: play, black history, ordinary people, poetry, children’s stories, and the connections that occur in unlikely ways in unlikely places. Her energy is infectious, her colors bold, and her ability to bring a smile to your face a rare and beautiful thing. Kudos to the MFA for allowing teens in its Curatorial Study Hall to write the wall text. Read: You can actually understand what is being said!

_________________________________________________________________

We vowed to ease back into the viewing groove rather than trying to take in everything. Nice try! We ended up dipping into several other shows, including a good one on Monet that has already closed and two others that were disappointing. “Masterpieces of Egyptian Sculpture” was billed as a total revamp of the MFA’s holdings. It’s not really–more like rearranging the den chairs and sofa. “Collecting Stories: The Invention of Folk Art” was an example of how museums should have the courage to fold their cards when they don’t have a matching pair. It’s really about collectors, not the art, plus the MFA’s folk art collection is so painfully thin it should offload it to an institution that knows the genre.

Rob Weir