Musee International D’Art Naif of Magog

61 Rue Merry N.

Magog, Quebec

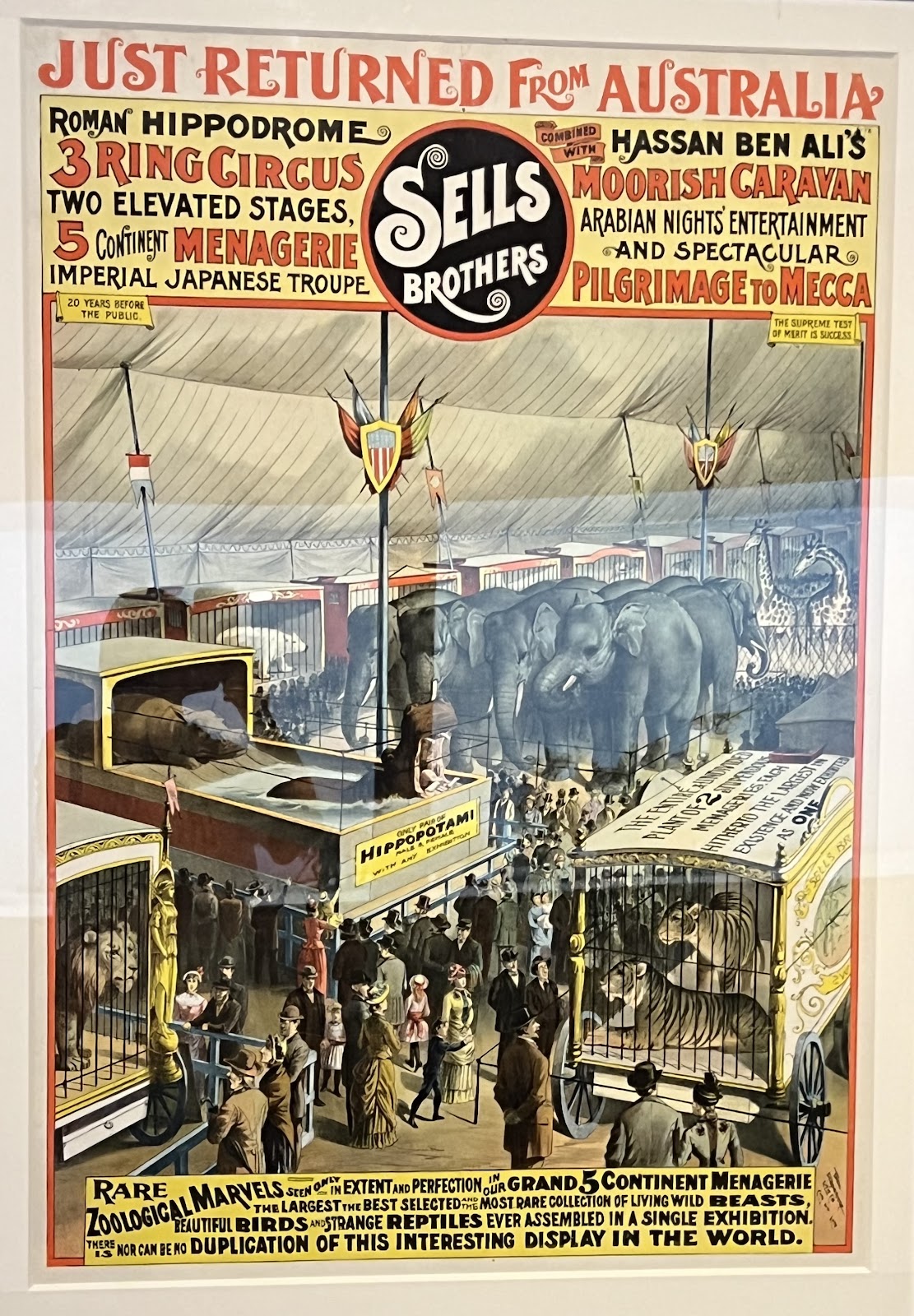

Let’s finish off this week of art by going full Monty (Python): “And now for something completely different.” The Musee International D’Art Naif (MIANM) is the only museum in all of Canada devoted to “primitive” art.

That term doesn’t mean prehistoric or tribal. It goes by other names: craft, folk art, naïve art, traditional, outsider art…. The last handle is pretty good in that it infers a primary characteristic of folk art; it’s usually “outside” of the formal art canon. Its practitioners are usually untrained–though famed painters such as Gaugin, Picasso, and Rousseau dabbled in it–and they pay little attention to the conventions that make up (so-called) fine art. Folk art is often pragmatic, even when it’s a painting on canvas–think rural people trying to make the old homestead more cheerful.

For some viewers primitive art evokes “my ten-year-old could do that” responses and that could be true in some cases. Primitivists frequently pay little or no attention to perspective, geometry, relative sizes, or sharp detail. Bold colors are another hallmark, as is an overall flatness. Mostly it fails the proverbial sniff test in that it doesn’t look like “real” art (whatever that means).

In the United States, the most famous folk artist is probably Grandma Moses (Anna Mary Robertson Moses 1860-1961). There’s an entire wing devoted to her work at the Bennington Museum of Art in southern Vermont. In Canada, thanks to the excellent 2016 biopic Maudie, Maud Lewis (1903-70) might wear the folk crown, though you might have to visit the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in Halifax to see a lot of it. (You can also see some on Google Images.)

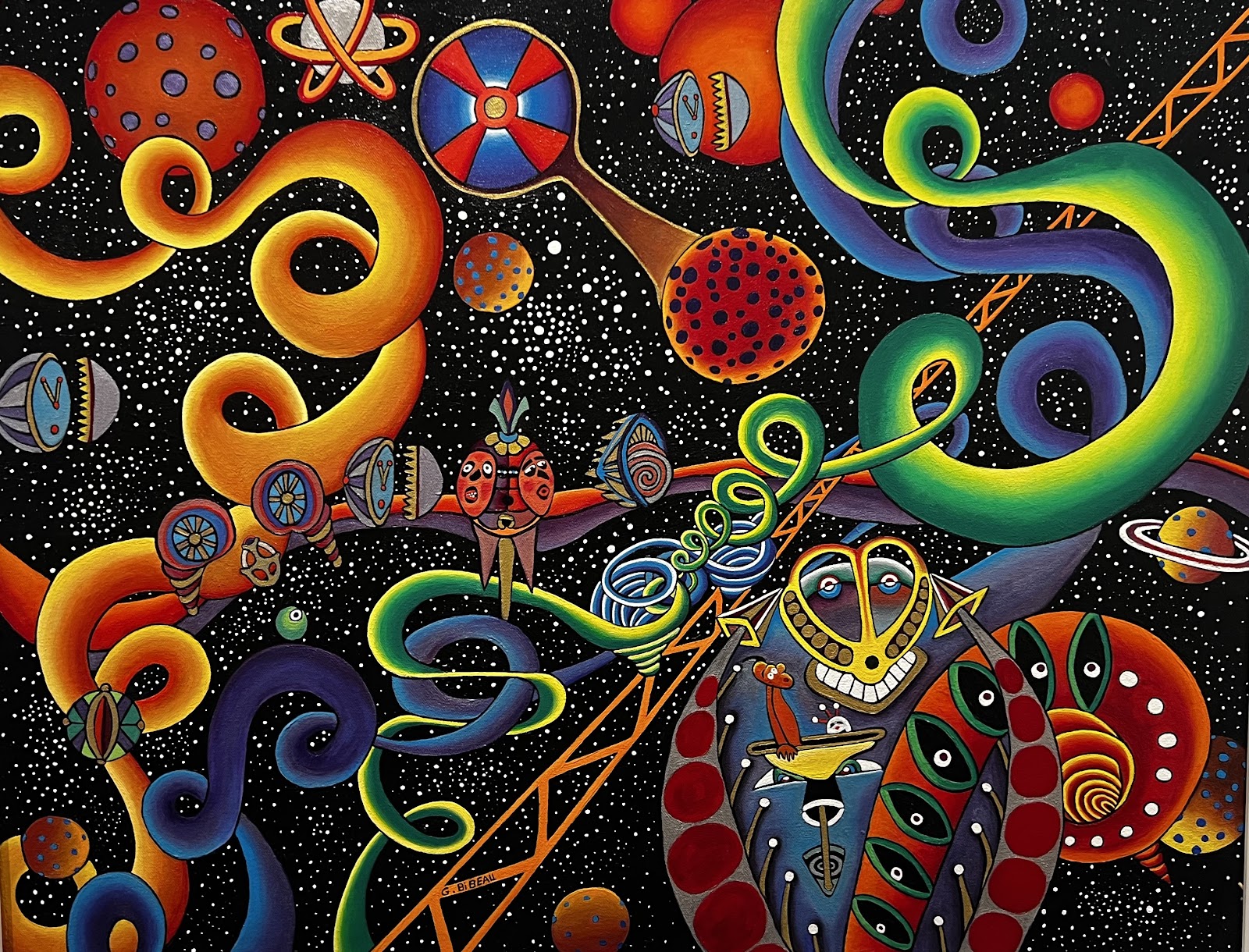

Folk art has been rescued from the categories of charming or quaint and is now collectible. Some of it fetches decent U.S. dollars and Canadian loonies on the open market, but mostly the categories have collapsed in ways that bring to life the old saw “I don’t know if it’s art but I know what I like.” The MIANM in Magog is just plain fun. There are no works from Moses or Lewis there, but the galleries have loads of things your ten-year-old could not paint. Quebec has a solid folk art tradition–Arthur Villeneuve, Robert-Émile Fortin–but when we visited earlier this month the MIANM was featuring the work of Gaetan Bibeau. What he does very well is capture our sense of imagination in ways that a good story can do. Here are some samples.

|

| Note how the perspective is off |

|

| Bibeau imagining what's put there in the heavens! |

|

| Radio City! |

|

| This reminds me of 'toon towns from my childhood |

Of course, MIANM also focuses on the international part of its moniker. And like I said, it’s just a lot of fun. If you find yourself in Magog–the head of Lake Memphremagog–stop in. If not, start looking for folk/primitive/outsider, etc. art. There’s much to be said for taking a break from all things academic!

|

| Barbara Sala, River of Penguins |

|

| Despoena Leonis |

|

| This Guylaine Cliche reminded me of Grandma Moses |

|

| Adele Bantjes is from South Africa |

|

| Jean-Claude Dupont take on werewolf tales |

|

| I've lost the painter's name, but this could be an illustration from a creepy graphic novel |