NIKOLAI ASTRUP: VISIONS OF NORWAY

Clark Museum of Art, Williamstown, MA

Through September 19, 2021.

Scandinavians are often the forgotten artists of Western Europe. Could you come up with a Norwegian artist not named Edvard Munch? Within Norway, Nikolai Astrup is ranked just below Munch, and you might detect a splash of Munch in the way Astrup deals with reflected moonlight, as seen in the woodcut “The Moon in May.”

|

| Funeral Day |

Astrup (1880-1928) did some traveling in his short life–he died of pneumonia at age 47–but he did most of his 210 paintings and 48 woodcuts in a single region, Western Norway, and largely in two places, near and in his childhood village in Jølster and in Sandalstrand (now called Astruptunet). (Ironically, one of his earliest paintings was titled “Funeral Day in Jølster.”) He also often depicted the same features repeatedly, a time-honored practice among painters; think Claude Monet and Rouen Cathedral, for example. Astrup was particularly fond of a mountain that loomed over a small fjord and experimented with coloring, moods, and perspectives.

His early life was like something from a Norwegian Gothic novel. In his youth, Norway was ruled by Denmark. That suited his father just fine, but Nikolai tended towards nationalism. He also wanted little to do with his father’s austere faith–he was a Lutheran priest at Ålthus church in the Jølster village of Sogn og Fjordane. You might have thought that Christian Astrup was Catholic; he sired 14 children, of which Nikolai was the eldest. He disappointed his father, who expected Nikolai to become a priest as well.

Nikolai’s church was the landscape, both the sod-roofed built environment and the features and light nature provided. One of his largest oils, “Clear Night in June” features all three, with swamp irises forming a perfect V-shape in front of a village tucked below a snow-topped mountainside and a fading orange-yellow sky. If you wonder about the snow and the light, remember that this is Norway, a land where many hills wear a frosty crown for most of the year and the summer sun dims rather than sets. His “Night in August” shows an analogous setting. The flowers have changed, but the snow remains.

In 1907, Nikolai married Engel Bunde (1892-1966), who bore

him eight children and still managed to become a respected textile artist in

her own right. A photo of the couple perhaps explodes your view of what a paint-flecked

artist looks like. With his wavy over-the-ear hair and wire-rimmed glasses he

looks like he could be either a school teacher or John Lennon’s grandfather. He

was devoted to Engel and often depicted her working in their Sandalstrand garden,

the latter of which he also repeatedly painted. The close up posted here shows

Engel harvesting rhubarb. She is also one of the figures in the enigmatically brooding

“By the Open Door.”

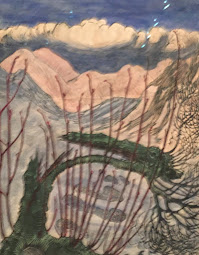

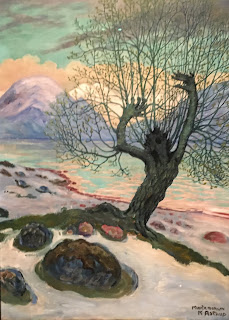

Astrup also drew upon Norwegian folktales and, in what must have horrified his dogmatic father and younger brothers who also became Lutheran priests, pagan rituals. He did several paintings and woodcuts of Midsummer bonfires and rituals, the latter pre-Christian solstice gatherings in which faeries were allegedly active and needed to be appeased. (Christians appropriated it as the Feast of John the Baptist.) He also used nature to give a nod to other pagan legends. The woodcut “Spring and Desire” transforms a hillside into a nude woman’s body, a reminder that May Day was once a fertility celebration that involved active carnality. “Spring and Willow” sports an eerie-looking tree that looks supernatural because its inspiration was the Ice/Snow Queen, an ogress.

It should be noted that Astrup’s use of wood block prints was actually unusual in Norway. Because he was working outside of tradition, Astrup was unrestrained in his use of textures and colors. Personally, I prefer his starker black and white prints to brightly colored works such as “Milling Weather,” which skirts the boundary of garishness, but I admire Astrup's willingness to experiment.

A few of his late works, notably “White Horse” in spring show him taking tentative steps away from representationalism. For me, there is a Marc Chagall-like quality to this work. It also tells us another thing about Nikolai Astrup. He was an artist active in and between several artistic traditions: impressionism, expressionism, primitivism, and modernism.

It’s always a joy to be astonished by lesser-known artists. You have a few months left to catch this show–and you should.

Rob Weir

No comments:

Post a Comment