Hood Art Museum

Hanover, New Hampshire

On View Now

The ultimate zero-sum-game is the attempt to rank comparative oppressions. Oppression is oppression. I say this because my next comment might otherwise seem insensitive. In today’s (Dis)United States, Latinos are now the largest minority group. Other high-profile movements include Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, Stop AAPI Hate, pro-choice activists, and transgender rights groups. Conspicuous by its relative absence is the minority group that is at or near the bottom of0 virtually every negative social indicator: Native Americans. About the only thing that hits the news is when some sports team decides to drop a stereotypical mascot, something that should have been done five decades ago.

A few weeks ago, I paid a visit to Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum. The college used to have teams called the Indians, but now it has the remarkable Jami Powell (Osage) as its Curator of Indigenous Art. If you think it doesn’t matter if such a person is part of a museum’s staff, I invite you to drive to Hanover, New Hampshire, and then make such a statement.

The Hood is about install a piece from Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith titled Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights. I was lucky enough to arrive just before the holiday break. Trade Canoe wasn’t yet on view, but most of the supporting exhibit was and I caught a preview. Here are just a few works of art that reminded me anew of how important it is to change the proverbial frame.

Take this powerful work from Yatika Starr Fields (Osage/Creek/Cherokee) titled White Buffalo Calf Women March. You will notice that the three women are literally cut off at the knees. How appropriate for those marching to halt the Dakota Access Pipeline that would bisect Lakota land. Alas, as of now the go ahead has been given for this needless oil pipeline. Is the white flag a sign of surrender? Maybe not. Notice it is held by what appears to be a pair of ghostly hands. Is it really that the sky and the flag and reflected in water? If so, why would a paved highway run into that water? Another way of looking at it is that the surrender flag has been cast down. Are the hands the ghosts of ancestors?

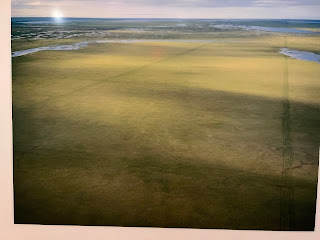

Subhankar Banerjee was born in India and is not Native American, but her photograph Known and Unknown Tracks is another reminder of what happens when we place oil ahead of indigenous rights or environmentalism. The wide expanse you see is the area near Teshepuk Lake in north-central Alaska. As you look at it, do you need me to remind you of the fragility of the tundra? Don’t fall for the malarkey that oil companies erase their eco-footprints.

Cara Romero (Chemehuevi) punctuates this in Oil Boom, a photographic “dreamscape” sandwich. Is the figure in the sepia water being born or drowning?

Arthur Amiotte (Lakota) offers a more conventional collage of layered photos and print clippings in Saint Agnes Manderson, S. D. Pine Ridge Rez. Manderson is a town in South Dakota and the composition is a take on the complicated issue of assimilation. Spend some time with this. Embedded within is a history lesson involving missionaries, schools that sought to obliterate Lakota culture, Natives who assimilated, those who partially did so, and traditionalists. It often confuses whites when they encounter Natives with Anglo-sounding names like Arthur who ID as Native. Now you know why.

In 2018, T C Cannon (Kiowa) was the subject of a fabulous retrospective at the Peabody Essex Museum. At the Hood we see his 1977 acrylic work Taos Winter Night. According to the curators, the spots might echo participation in a Sun Dance ritual. It can also be enjoyed on its own for its strong compositional elements.

Roxane Swentzell (Santa Clara Pueblo)–see what I mean about names–works in ceramics. Her Sitting on My Mother’s Back is figurative on many levels: woman as nurturer, shelter, defiant figure, Mother Earth…. I couldn’t stop looking at this one.

Swentzell collaborated with Rose Simpson (Santa Clara Pueblo) on the 21-foot-long Timeline Necklace. It’s a mixed media combination of ceramics, wood, wire, leather, and rope that also looks at women and motherhood. It also contains subtle reminders of single women, poverty, and resilience.

Leave it the dynamic Faith Ringgold to connect the color dots. She is African American and better known as a quilter, but her photolithograph United States of Attica, was made in 1972. It was inspired by the infamous 1971 prison riot that left 43 people dead and 91 wounded. It reminds us that H. Rap Brown (now Jamil Al-Amin) was right to assert that “Violence is as American as cherry pie.” This closeup is part of a larger map in the Pan-African colors of red and green and shows the toll in the Southeast.

I have loved Inuit art since the days when I taught high school Canadian studies. The Hood show Inuit Art/Inuit Quajimajatuqangit samples Inuit works on paper and stone carving.

I invite you to draw your own meanings from the following

pieces, which I have labeled by artist (if known).

| ||

| Helen Kalvak Nightmare | |

| ||||

| Sarah Joe Qinujua Ready to Leave for the Hunt |

No comments:

Post a Comment