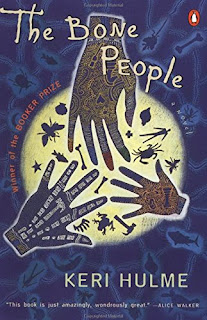

the bone people [sic]

By Keri Hulme

Penguin books, 1986, 445 pages.

★★★★★

Hulme wanted her title in lower case!

On December 27, 2021, Keri Ann Ruhi Hulme died in a dementia unit in Waimate, New Zealand. Hers was a difficult life. She came from a multicultural background; her father John carpenter was a carpenter of English ancestry and her mother Mary Ann Miller was a credit manager with Scottish, Faroe Islands, and Máori heritage. She was christened “Kerry” but, in 2001 changed it the Keri, which was more Máori. In her words, “Of all my family, I look the least Máori but feel the most Máori.” Before he died when Keri was 11, John Hulme called his daughter “my Máori princess” and she spent vacations with her mother’s Máori relatives in Moeraki on New Zealand’s North Island. Keri took care of her mother’s home until Mary died in an accident.

Ms. Hulme was a hard person to get along with. She dropped out of law school because she felt “estranged,” which also describes her relationship with her five younger siblings. She was a poet, short story writer, novelist, and painter. Hulme was a solid woman who played guitar, had authority issues, and smoked a pipe and cigarillos. After leaving school she picked tobacco and hops, was obsessed by whitebait (fry fish), and built most of her house with her own hands on a plot of land that she won in a 1973 lottery near the remote former gold mining town of Ókárito (South Island). She was an atheist, asexual, and skeptical of romance. In her spare time, she wrote and painted, some of the latter good enough for exhibitions. Her home had more than 12,000 books, Keri’s greatest company. Locals knew her for her fierce temper, strong opinions, cooking wizardry, and heavy drinking.

It took 17 years for Hulme to see the bone people in print, as it was rejected by virtually every publisher in New Zealand. Conservatives wanted no part of it and liberal whites accused her of cultural appropriation. In Wellington, a group of feminists formed the Spiral Collective to publish Hulme’s debut. In 1985, Hulme got a phone call advising that she had won the Booker Prize, Europe's most prestigious book award. Her response was, “Oh–bloody hell.” As you might surmise, she wanted nothing to do with fame, critics who lambasted her style, nor those who wondered how she could have won over writers such as Doris Lessing and Iris Murdoch.

If you’re wondering why I’ve written an obituary instead of reviewing the book, the answer is simple; one of the three main characters has every characteristic I described above. She’s even named (ahem!) Kerewin Holmes. I first read the bone people in 2001 and reread it in 2022. The experience was even more rewarding the second time around. I hesitate to call it fiction in any sense other than story details. It’s autobiography, first person, third person, poetry, political commentary, anthropology, naturalism, magic, and mysticism. Truly, it is one of the most extraordinary things I’ve ever set eyes upon.

Go slowly; it’s not an easy read. Among other things, there is a mix of English and Máori dialogue. Keep a bookmark in the back for translation, but pay attention; she expected readers to learn as they went along and didn’t hold hands a second time. (You could ignore the Máori, but why would you?) That’s because one intention was to build a “bridge” (her words) between Máori and non-Máori Pákehá. (This Pákehá wishes white folks would cease the racist practice of appointing themselves as guardians of people of color.)

The heart of the story–and I emphasize that that’s only part of the book–is the relationship between Kerewin, Joseph Ngakaukawa Gillayley, and his found son Simon Peter. As you can see, racial lines are blurry. Joe identifies as Máori and so does Kerewin. As for Simon, who knows? Joe’s wife and child died in an accident and “Simon” is the name he gave to the only survivor of a shipwreck. No one knows much about Simon; he’s intelligent, but mute, writes, but was too young to recall his life before he knew Joe. Simon is also very difficult. He is ridiculed by other kids and fights back ferociously; he also skips school, drinks, smokes, and steals anything that’s not bolted down.

Like Joe, Simon is fun-loving and pleasant one moment, and violent and destructive the next. Joe loves Simon, but he also beats him. Simon’s wandering ways bring him to Kerewin’s odd compound–it sports a handmade tower–and soon he and Joe intrude on her solitude. I will say nothing more except if you think this is going to turn into anything resembling a family fairy tale, you're on the wrong island. The book is about broken people; in real life, healing doesn’t happen in a straight line and sometimes not at all. Nor, in Hulme’s imagining, are there hard-fast boundaries between reality, visions, and dreams. It’s a bridge between Máori and Pákehá, but an intentionally rickety one.

I cannot overemphasize what a remarkable book this is. Do take my advice and read in small doses. Maybe even study the Máori in the back matter. I can help a little with that (see below*). You will not be the same when you finish.

Rob Weir

*I’m bad with languages, but it helps to vocalize words. Máori looks tough but its long words are generally easier to pronounce that you might think. In most cases, you can break the words into groups of adjoining letters without stress syllables. Pákehá (white people) is Pá/ke/há and pronounced something like Pa-key-ha.

There are exceptions, of course. (Think of the illogical of English.) Double vowels run together. Mao/ri comes out sort of like the Chinese name “Mao” + ree (i is usually a long e sound and e the short a of English.) There are lots of ng words and you mush them together. Words beginning with w are tricky. If it stands alone, it’s w; if it’s wh, an f sound, which I found out when I visited the Máori homeland of whakarewarewa, which comes out a bit like Fucka-rah-weir-ah!)

No comments:

Post a Comment