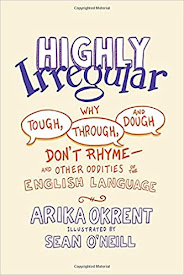

HIGHLY IRREGULAR: WHY TOUGH, TROUGH, AND DOUGH DON’T RHYME

AND OTHER ODDITIES OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE (2021)

By Arika Okrent, Illustrated by Sean O’Neill

Oxford, 244 pages (+ back matter)

★★★★★

If someone on your holiday list is a words person, have I got a book for you! The title says it all. English is a top contender for the globe’s quirkiest tongue. Most languages turn to “mutts” over time, but English might be the mangiest pooch in the lingo kennel.

Perhaps the author’s surname seems familiar. Arika Okrent is the niece of writer, editor, and media personality Daniel Okrent. (He also invented Rotisserie Baseball.) Arika has something “Uncle Danny” (her handle) doesn’t: a Ph.D. in linguistics. At a glance, Highly Irregular is a shrunken coffee table book, but Okrent knows her stuff. Her special gift is to take expertise and spin it in cheeky tones that make her book a delight.

She divides her work into seven sections, beginning with a reoccurring exclamatory question: “What the Hell, English.” She explores silent letters in words such as colonel, should, surprise, and those with y vowels (like gym). She also analyzes head-scratchers such as why we drive on a parkway but park in a driveway. And what about the weird ways we use big and large? (No one is ever a “large” spender.)

How did English get to be such a literary Jello salad? In Section II, Okrent tells us to “Blame the Barbarians,” the Germanic tribes who got the English ball rolling. We don’t pronounce the g in gnat, gist has a j sound, it’s a gh in give, but the one in girl is a hard sound. In most cases, the original Germanic peoples sounded words differently, or our current words derived from completely different ones no longer used. I won’t even get into words ending in ing or ly, but Okrent does.

The Germans don’t bear all the blame. In Section III Okrent tells us to “Blame the French.” They gave us a bunch of synonyms the likes of which confuse those seeking to learn English. Why does veal come from a calf, and pork from a pig? There are words whose context determines how we stress them–insult, transform, protest–and phrases that need prepositions and those that don’t. Do we really need to say “without a doubt” when we already have doubtless? Why is love pronounced as if it is “l-of?”

We can also “Blame the Printing Press,” which Okrent does in Section IV. Standardized spelling led to the “Great Vowel Shift,” which left us with ghost sounds–like the very h in ghost. It also left us with aspirated sounds that don’t appear on the page, like that same h sound in girl. The printing press helps explain why grew and sew don’t rhyme, nor do steak and freak. I was surprised (or sup-prised if you must) that Ed Sullivan got it right when he promised a really big “shew” (show). If you want to know why Worcester is pronounced in ways unlike how it looks, or why the Brits make Cholmondeley sound like “Chumley,” this chapter explains.

In Section VI we “Blame the Snobs” who add extra letters, use Latin plurals, show off by pronouncing letters no one else does, set the rules on homophones (words that sound alike), and lay down the law on how to say and spell foreign words. They are the sort who pronounce the p in receipt and the l in salmon, cough up phlegm, and insist that more than one octopus or rhinoceros are octopi and rhinoceri. They tell us when we are here and when we hear, and exhort us to be discreet when we are discussing discrete data–and I don’t mean datum. Noah Webster gets either credit or a kick in the pajamas (foreign word) for dumping the u in colour and sending people off to jail instead of gaol.

In the end, we also have to “Blame Ourselves.” Why on earth would we keep words that now usually exist only in the negative, like uncouth, unkempt, and disgruntled? It makes no sense that we “clean” things that are dirty but never “undirty” them, or raise "up" a window. (You can’t raise it down!) Why is the plural of goose, geese but an extra moose or two isn’t meese? We have weird negative phrases such as “I didn’t sleep a wink.” (Presumably there must be people who go to bed, sleep one wink, and arise.) We retain abbreviations that are outdated. You might not wish to tell a woman who introduces herself as Mrs. Smith that her abbreviation is short for “mistress.” Most of the time when someone says literally, they mean figuratively.

What a fun book. Give it someone in your family but save it for the last gift, as you’ll spend the rest of the day laughing at the absurdity of your native tongue. Because, what the hell, English?

Rob Weir