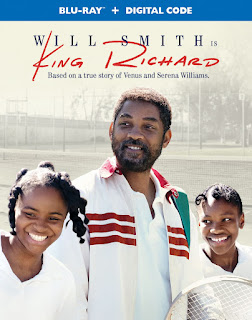

KING RICHARD (2021)

Directed by Reinaldo Marcus Green

Warner Bros. Pictures, 145 minutes, PG-13 (language, violence, sexual reference)

★★★

Before the slap heard ‘round the world, Will Smith starred in the biopic King Richard. As you no doubt know, he won an Oscar for that performance. It might renew interest in a movie that flopped badly at the box office. Should it? I have mixed feeling about that.

Smith assumed the role of Richard Williams, the father of tennis champions Venus and Serena Williams, played by young actresses Saniyya Sidney and Demi Singleton respectively. The movie only takes us through 14-year-old Venus’ professional debut in 1994 and her second-round loss to Aranxa Sánchez Vicario (Marcela Zacharías), who resorted to dirty tricks to get back into a match she was losing. The subsequent rise of Venus and Serena to the top of tennis world is relegated to a postscript.

The movie has been criticized for being too much about Richard, shortchanging the coaching done by his then-wife Oracene (Aunjanue Ellis), and portraying the skills of his daughters as his own doing. These are valid complaints. King Richard is at its best in capturing the Zeitgeist of the 1980s when race was an obstacle the entire Williams family had to hurdle. In the 1950s, Althea Gibson starred, but she dented rather than knocked down racial barriers and quit competitive tennis for golf. Women’s tennis remained predominantly lily white until the emergence of the Williams sisters.

The tennis establishment was reluctant to accept that two Black kids from the Compton section of Los Angeles drilled and coached by their parents could compete with well-heeled and extensively-trained white kids. A lot of sports films suffer from Hoosiers syndrome, the big buildup in which adversity yields to triumph; King Richard is no exception, though it gets the racism right. We see Richard meet polite rejection–racism with a smile–as he sought professionals to help his daughters receive the same advantages as white girls. We watch Richard try hard to keep himself and his family safe and out of trouble in a neighborhood marked by drugs, gangs, and guns. Rick Macci (Jon Bernthal) took a chance, sponsored their move to Florida and into a new life. You know the rest.

The film skirts or merely mentions a lot of controversy. It shows Richard as obsessed and pigheaded, which most insiders say was so. He also thought he knew better than anyone else. He deserves kudos for making sure his brood–Venus and Serena were his biological daughters but he also helped raise three that Oracene had with her first husband–got to be kids first. I can’t comment on the veracity of those who said he wasn’t the coaching genius he fancied himself or that he wasn’t the shrewd bargainer the film depicts. The film hints that Oracene was more instrumental in the latter.

If Althea Gibson was the Jackie Robinson of tennis for Black women, Venus Williams was its Michael Jordan. Her success made from age 14 on made it cool and possible for other Black girls to bring color to center court. She has won 49 titles to date, though at age 41 and many injuries she is now ranked #407 in a sport in which most tour players are about half her age. With 23 Grand Slam titles, Serena is arguably the greatest female tennis star in history. * (At age 40 she is ranked #224, but she picks her tournaments and thus doesn’t rack up ranking points.)

It's a wonderful story, but merely a middling film. I’ll just come and say that Will Smith gave a good performance, but not one worthy of the Best Actor Oscar he was given. Both Ellis, who was nominated for Best Supporting Actress, and young Sidney were far more deserving of honors than he. In my view, Smith didn’t warrant a nomination let alone the hardware.

At 145 minutes King Richard suffers from being too long. Zach Baylin’s script sheds too much light on Richard and comes close to deifying him. His role was important, but let us not forget that his was reflected glory. Serena is a near afterthought and the inference is that she was several years, not one, younger than Venus. I can’t help but think that a film titled The Williams Sisters with Richard in a supporting role would have been a much stronger film. Credit, though, to cinematographer Robert Elswit for making the tennis look like actual tennis, even if the power of pre-teen Venus was enhanced a bit.

Overall, King Richard is a quintessential 3 of 5 movie, worthwhile but not a classic.

Rob Weir

*FYI, the debate is whether the greatest female tennis champion is Serena or Martina Navratilova. Flip a coin.