EDWARD GOREY HOUSE

Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts

I’d like to introduce some new material for the Art Smarts section of the blog. If you will, call it small museums. Maybe you’re one of those who gets overwhelmed by places like New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Boston’s MFA, or the Chicago Institute of Art. Often, you’re in one of those places, have a limited amount of time, try to cram in as much as you can, and end up viewing art the way you might observe a roadside fender-bender. Or, perhaps, you’ve simply grown weary of the “great artists” approach of such places. Small museums are antidotes. Many are more creative and few of them will exhaust you.

If you are headed for Cape Cod this summer or fall, be sure to stop at the Edward Gorey House in Yarmouth Port. It will be an hour or so well spent. Does the name Edward Gorey (1925-2000) ring a bell? If you’ve ever seen an episode of Mystery on PBS, Gorey’s illustrations introduce the episodes, complete with damsels in distress, falling cornices, cracking lightning, and lurking shady characters.

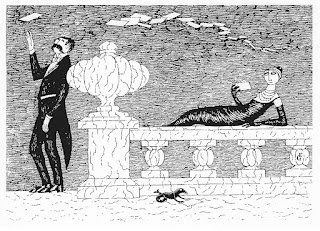

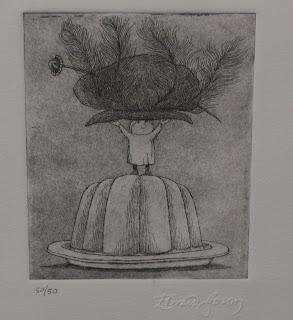

Gorey is often labeled an illustrator, but that doesn’t quite get it. He specialized in etchings and drawings, but he also loved theatre and bagged two Tony Awards, one for costume design and the other for set design. In addition, he wrote or illustrated an untold number of books for children of non-snowflake parents. You know, the kind of kids who love a bit of, well, gore and a good scare now and then. Not that there was anything explicit about his work. I like to think of his verse, stories, and illustrations for the younger set as Edwardian surrealism. It’s analogous to his lead-ins for Mystery in that it’s vaguely creepy and endlessly amusing. The latter quality makes it irresistible for adults as well.

Gorey was embraced by the Goth movement, but that doesn’t quite fit either. It’s more like tongue-in-cheek Gothic. Gorey simply couldn’t resist figures with capes pulled across their faces, architecturally challenging hats, and faces as enigmatic as the Mona Lisa. Toss in some broken crockery, animals plucked from some madcap Bestiary, falling objects, Seuss-like odd words, and vile-weather settings and it’s welcome to the vision of Edward Gorey. He also delighted in offbeat humor–many of his books were credited to those with anagrams of his own name, such as Dodgear Wryde–and in finding offbeat ways of depicting prosaic things such as hedges, rocks, articles of clothing, or simply people doing nothing.

Gorey was born in Chicago and studied at its Art Institute. He served in the Army during World War II, then attended Harvard. At the latter he got involved with the Poets Theatre and rubbed elbows with luminaries such as Alison Lurie and Frank O’Hara. He was a great admirer of Broadway choreographer George Balachine and worked on several of his shows, including Dracula. (What could be more appropriate?) His personal life was open to great speculation, the consensus being he was probably an asexual gay man. Meh. Who cares?

Each season the Gorey House features one aspect of Gorey’s work and for 2022 the theme is dance. Think you don’t care about theatrical dance and ballet? Forget tulle and tutus; Gorey brought his skewed views to illustrations of dance as snobs would never recognize it!

The Gorey House also maintains shelves, niches, and cabinets of curiosities as he left them. Like a lot of artists, he was fascinated by shapes, picked up found objects whose designs he liked, and purchased items that simply caught his fancy. He adored cats, owned lots of them, and was a serial fascinationist who thought nothing of procuring bronze bugs, masks, and all manner of bric-a-brac. Treat yourself to a visit. You’ll leave smiling, which is the right attitude to have as you battle Route 6 traffic to wherever you’re headed.

Rob Weir